Utah’s Criminal Laws Must Act Uniformly

Article I, section 24 of the Utah Constitution which states: “All laws of a general nature shall have uniform operation.” Article I, section 24 “establishes different requirements than does the federal Equal Protection Clause.” State v. Mohi, 901 P.2d 991, 997 (Utah 1995). In Utah, a law can only be constitutional under article I, section 24, if in addition to being neutral on its face, its “operation of the law be uniform. A law does not operate uniformly if persons similarly situated are not treated similarly.” Id.

The Test for Determining if Utah Law’s Apply Uniformly

In determining whether a law is in compliance with Utah’s uniform operation of laws provision, the Court must apply two tests: “First, a law must apply equally to all persons within a class. Second, the statutory classifications and the different treatment given the classes must be based on differences that have a reasonable tendency to further the objectives of the statute,” that is, the Court must determine whether there is a “reasonable relationship” between the purpose of the law “and the means adopted by the legislature to enact that purpose.” Id.

In Mohi, the defendant challenged the constitutionality of a statute which divided juveniles charged with capital crimes or first degree felonies into two classes: one class would be tried as a juveniles in juvenile court, the other would be tried as adults in district court.

The First Mohi Prong

Regarding the first test, the State contended that the statute was neutral on its face because there is no class created until the prosecutor decides how to proceed on a particular case. The Court rejected this argument outright stating:

The amended statute plainly states that a certain class of juveniles will be treated in one way (remain in juvenile jurisdiction) while another class of like-accused juveniles will be treated in another (singled out by prosecutors to be tried as adults). [Citations] Although a prosecutor’s decision triggers the assignment of any given defendant to one class or another, the statutory scheme itself contemplates the two classes.

Id. The Mohi Court also found that the act treated the different subclasses of juveniles differently. Specifically, the Court found that by the very terms of the statute the different classes of juveniles are accused of the same offenses. The Court further found that the statute has

Absolutely nothing…to identify the juveniles to be tried as adults; describes no distinctive characteristics to set them apart from juveniles in the other statutory class who remain in juvenile jurisdiction. However, there are critically important differences in the treatment of those juveniles tried as adults compared to those left in the juvenile system. For instance, cases tried in the juvenile court are considered civil rather than criminal proceedings. [Citations]. This has significant ramifications for an individual’s future criminal record.

Id. at 998.

The Second Mohi Prong

Mohi next addressed the second test – whether there was a “reasonable relationship” between the purpose of the law and the means adopted by the legislature to enact that purpose. The purpose of the act at issue in Mohi was to “promote public safety and individual accountability by the imposition of appropriate sanctions on persons who have committed acts in violation of law” and “consistent with the ends of justice, strive to act in the best interests of the children in all cases and attempt to preserve and strengthen family ties where possible.” The State argued that charging juveniles as adults was related to the statute’s purpose because of the “need to try certain violent juveniles as adults.” Id. at 999. The Court, although agreeing with the need expressed by the State, found that:

[The] legislature has failed to specify which violent juveniles require such treatment, instead delegating that discretion to prosecutors who have no guidelines as to how it is to be exercised. Legitimacy of a goal cannot justify an arbitrary means. The State asserts that this problem is cured by the fact that prosecutors often have legitimate reasons for wanting to leave persons eligible for adult prosecution in juvenile court. But the statute does not require the prosecutor to have any reason, legitimate or otherwise, to support his or her decision of who stays in juvenile jurisdiction and who does not. Legitimacy in the purpose of the statute cannot make up for a deficiency in its design. [The law] is wholly without standards to guide or instruct prosecutors as to when they should or should not use such influential powers.

Id. The Court then held: “We conclude that the provisions…of the Code giving prosecutors undirected discretion to choose where to file charges against certain juvenile offenders are unconstitutional under article I, section 24 of the Utah Constitution.” Id. at 1004.

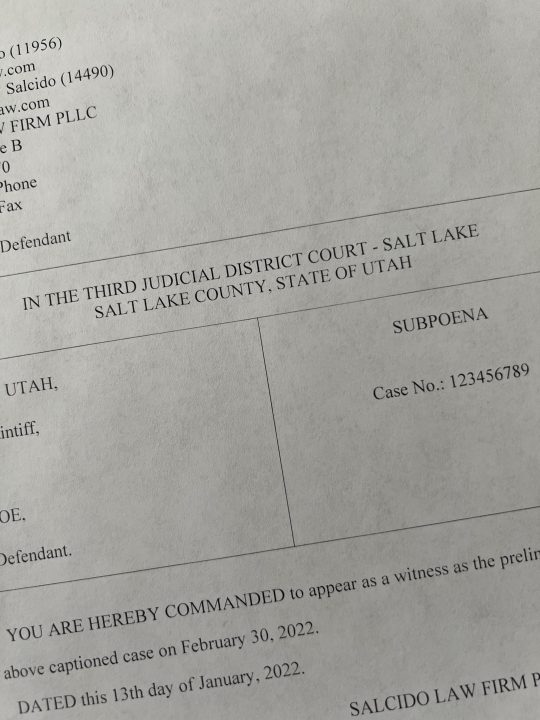

Salcido Law Firm is Dedicated to Equal Protection

There are times when a municipality, county, or the state may pass a law which violates equal protection. If you believe you have been the victim of a violation of Utah’s equal protection call our Criminal Defense for help at 801.413.1753. Our defense lawyers are ready and willing to protect your rights.